Engineers are plugging holes in drinking water treatment

Off a gravel road at the edge of a college campus — next door to the town’s holding pen for stray dogs — is a busy test site for the newest technologies in drinking water treatment.

In the large shed-turned-laboratory, University of Massachusetts Amherst engineer David Reckhow has started a movement. More people want to use his lab to test new water treatment technologies than the building has space for.

The lab is a revitalization success story. In the 1970s, when the Clean Water Act put new restrictions on water pollution, the diminutive grey building in Amherst, Mass. was a place to test those pollution-control measures. But funding was fickle, and over the years, the building fell into disrepair. In 2015, Reckhow brought the site back to life. He and a team of researchers cleaned out the junk, whacked the weeds that engulfed the building and installed hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of monitoring equipment, much of it donated or bought secondhand.

“We recognized that there’s a lot of need for drinking water technology,” Reckhow says. Researchers, students and start-up companies all want access to test ways to disinfect drinking water, filter out contaminants or detect water-quality slipups. On a Monday afternoon in October, the lab is busy. Students crunch data around a big table in the main room. Small-scale tests of technology that uses electrochemistry to clean water chug along, hooked up to monitors that track water quality. On a lab bench sits a graduate student’s low-cost replica of an expensive piece of monitoring equipment. The device alerts water treatment plants when the by-products of disinfection chemicals in a water supply are reaching dangerous levels. In an attached garage, two startup companies are running larger-scale tests of new kinds of membranes that filter out contaminants.

Parked behind the shed is the almost-ready-to-roll newcomer. Starting in 2019, the Mobile Water Innovation Laboratory will take promising new and affordable technologies to local communities for testing. That’s important, says Reckhow, because there’s so much variety in the quality of water that comes into drinking water treatment plants. On-site testing is the only way to know whether a new approach is effective, he says, especially for newer technologies without long-term track records.

The facility’s popularity reflects a persistent concern in the United States: how to ensure affordable access to clean, safe drinking water. Although U.S. drinking water is heavily regulated and pretty clean overall, recent high-profile contamination cases, such as the 2014 lead crisis in Flint, Mich. (SN: 3/19/16, p. 8), have exposed weaknesses in the system and shaken people’s trust in their tap water.

Tapped out

In 2013 and 2014, 42 drinking water–associated outbreaks resulted in more than 1,000 illnesses and 13 deaths, based on reports to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The top culprits were Legionella bacteria and some form of chemical, toxin or parasite, according to data published in November 2017.

Those numbers tell only part of the story, however. Many of the contaminants that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates through the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act cause problems only when exposure happens over time; the effects of contaminants like lead don’t appear immediately after exposure. Records of EPA rule violations note that in 2015, 21 million people were served by drinking water systems that didn’t meet standards, researchers reported in a February study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That report tracked trends in drinking water violations from 1982 to 2015.

Current technology can remove most contaminants, says David Sedlak, an environmental engineer at the University of California, Berkeley. Those include microbes, arsenic, nitrates and lead. “And then there are some that are very difficult to degrade or transform,” such as industrial chemicals called PFAS.

Smaller communities, especially, can’t always afford top-of-the-line equipment or infrastructure overhauls to, for example, replace lead pipes. So Reckhow’s facility is testing approaches to help communities address water-quality issues in affordable ways.

Some researchers are adding technologies to deal with new, potentially harmful contaminants. Others are designing approaches that work with existing water infrastructure or clean up contaminants at their source.

How is your water treated?

A typical drinking water treatment plant sends water through a series of steps.

First, coagulants are added to the water. These chemicals clump together sediments, which can cloud water or make it taste funny, so they are bigger and easier to remove. A gentle shaking or spinning of the water, called flocculation, helps those clumps form (1). Next, the water flows into big tanks to sit for a while so the sediments can fall to the bottom (2). The cleaner water then moves through membranes that filter out smaller contaminants (3). Disinfection, via chemicals or ultraviolet light, kills harmful bacteria and viruses (4). Then the water is ready for distribution (5).

There’s a lot of room for variation within that basic water treatment process. Chemicals added at different stages can trigger reactions that break down chunky, toxic organic molecules into less harmful bits. Ion-exchange systems that separate contaminants by their electric charge can remove ions like magnesium or calcium that make water “hard,” as well as heavy metals, such as lead and arsenic, and nitrates from fertilizer runoff. Cities mix and match these strategies, adjusting chemicals and prioritizing treatment components, based on the precise chemical qualities of the local water supply.

Some water utilities are streamlining the treatment process by installing technologies like reverse osmosis, which removes nearly everything from the water by forcing the water molecules through a selectively permeable membrane with extremely tiny holes. Reverse osmosis can replace a number of steps in the water treatment process or reduce the number of chemicals added to water. But it’s expensive to install and operate, keeping it out of reach for many cities.

Fourteen percent of U.S. residents get water from wells and other private sources that aren’t regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act. These people face the same contamination challenges as municipal water systems, but without the regulatory oversight, community support or funding.

“When it comes to lead in private wells … you’re on your own. Nobody is going to help you,” says Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech engineer who helped uncover the Flint water crisis. Edwards and Virginia Tech colleague Kelsey Pieper collected water-quality data from over 2,000 wells across Virginia in 2012 and 2013. Some were fine, but others had lead levels of more than 100 parts per billion. When levels are higher than its 15 ppb threshold, the EPA mandates that cities take steps to control corrosion and notify the public about the contamination. The researchers reported those findings in 2015 in the Journal of Water and Health.

To remove lead and other contaminants, well users often rely on point-of-use treatments. A filter on the tap removes most, but not all, contaminants. Some people spring for costly reverse osmosis systems.

New tech solutions

These three new water-cleaning approaches wouldn’t require costly infrastructure overhauls.

Ferrate to cover many bases

Reckhow’s team at UMass Amherst is testing ferrate, an ion of iron, as a replacement for several water treatment steps. First, ferrate kills bacteria in the water. Next, it breaks down carbon-based chemical contaminants into smaller, less harmful molecules. Finally, it makes ions like manganese less soluble in water so they are easier to filter out, Reckhow and colleagues reported in 2016 in Journal–American Water Association. With its multifaceted effects, ferrate could potentially streamline the drinking water treatment process or reduce the use of chemicals, such as chlorine, that can yield dangerous by-products, says Joseph Goodwill, an environmental engineer at the University of Rhode Island in Kingston.

Ferrate could be a useful disinfectant for smaller drinking water systems that don’t have the infrastructure, expertise or money to implement something like ozone treatment, an approach that uses ozone gas to break down contaminants, Reckhow says.

Early next year, in the maiden voyage of his mobile water treatment lab, Reckhow plans to test the ferrate approach in the small Massachusetts town of Gloucester.

In the 36-foot trailer is a squeaky-clean array of plastic pipes and holding tanks. The setup routes incoming water through the same series of steps — purifying, filtering and disinfecting — that one would find in a standard drinking water treatment plant. With two sets of everything, scientists can run side-by-side experiments, comparing a new technology’s performance against the standard approach. That way researchers can see whether a new technology works better than existing options, says Patrick Wittbold, the UMass Amherst research engineer who headed up the trailer’s design.

Charged membranes

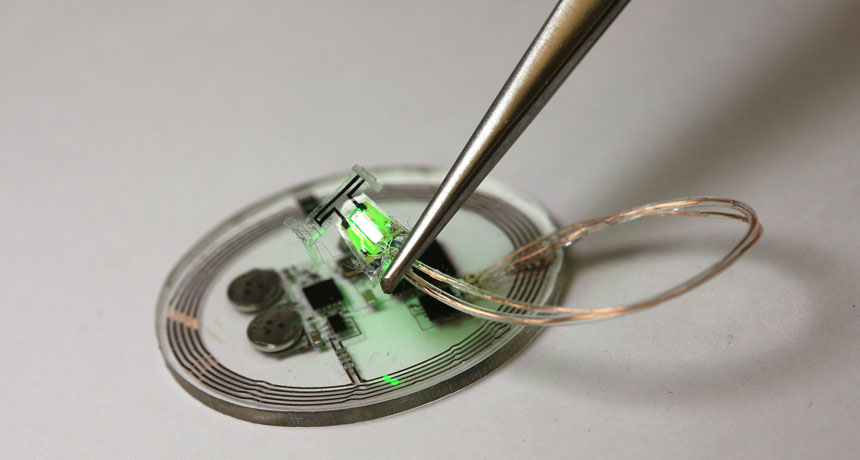

Filtering membranes tend to get clogged with small particles. “That’s been the Achilles’ heel of membrane treatment,” says Brian Chaplin, an engineer at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Unclogging the filter wastes energy and increases costs. Electricity might solve that problem and offer some side benefits, Chaplin suggests.

His team tested an electrochemical membrane made of titanium oxide or titanium dioxide that both filters water and acts as an electrode. Chemical reactions happening on the electrically charged membranes can turn nitrates into nitrogen gas or split water molecules, generating reactive ions that can oxidize contaminants in the water. The reactions also prevent particles from sticking to the membrane. Large carbon-based molecules like benzene become smaller and less harmful.

In lab tests, the membranes effectively filtered and destroyed contaminants, Chaplin says. In one test, a membrane transformed 67 percent of the nitrates in a solution into other molecules. The finished water was below the EPA’s regulatory nitrate limit of 10 parts per million, he and colleagues reported in July in Environmental Science and Technology. Chaplin expects to move the membrane into pilot tests within the next two years.

Obliterate the PFAS

The industrial chemicals known as PFAS present two challenges. Only the larger ones are effectively removed by granular activated carbon, the active material in many household water filters. The smaller PFAS remain in the water, says Christopher Higgins, an environmental engineer at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. Plus, filtering isn’t enough because the chunky chemicals are hard to break down for safe disposal.

Higgins and colleague Timothy Strathmann, also at the Colorado School of Mines, are working on a process to destroy PFAS. First, a specialized filter with tiny holes grabs the molecules out of the water. Then, sulfite is added to the concentrated mixture of contaminants. When hit with ultraviolet light, the sulfite generates reactive electrons that break down the tough carbon-fluorine bonds in the PFAS molecules. Within 30 minutes, the combination of UV radiation and sulfites almost completely destroyed one type of PFAS, other researchers reported in 2016 in Environmental Science and Technology.

Soon, Higgins and Strathmann will test the process at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado, one of nearly 200 U.S. sites known to have groundwater contaminated by PFAS. Cleaning up those sites would remove the pollutants from groundwater that may also feed wells or city water systems.