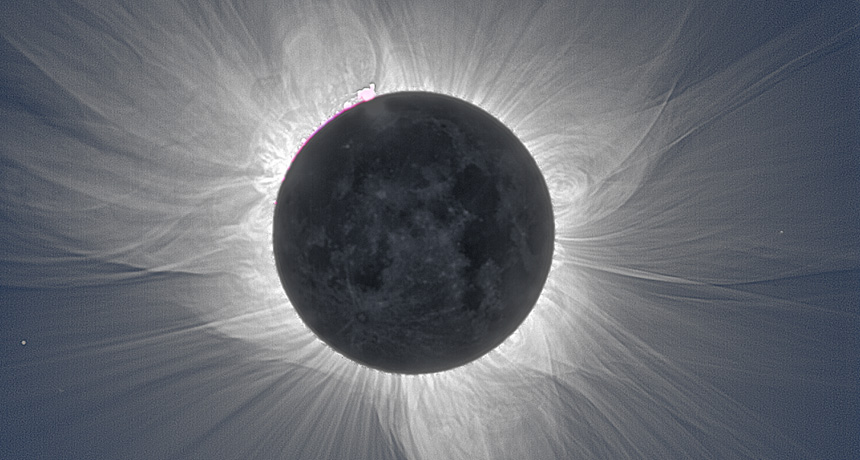

What happens in Earth’s atmosphere during an eclipse?

As the moon’s shadow races across North America on August 21, hundreds of radio enthusiasts will turn on their receivers — rain or shine. These observers aren’t after the sun. They’re interested in a shell of electrons hundreds of kilometers overhead, which is responsible for heavenly light shows, GPS navigation and the continued existence of all earthly beings.

This part of the atmosphere, called the ionosphere, absorbs extreme ultraviolet radiation from the sun, protecting life on the ground from its harmful effects. “The ionosphere is the reason life exists on this planet,” says physicist Joshua Semeter of Boston University.

It’s also the stage for brilliant displays like the aurora borealis, which appears when charged material in interplanetary space skims the atmosphere. And the ionosphere is important for the accuracy of GPS signals and radio communication.

This layer of the atmosphere forms when radiation from the sun strips electrons from, or ionizes, atoms and molecules in the atmosphere between about 75 and 1,000 kilometers above Earth’s surface. That leaves a zone full of free-floating negatively charged electrons and positively charged ions, which warps and wefts signals passing through it.

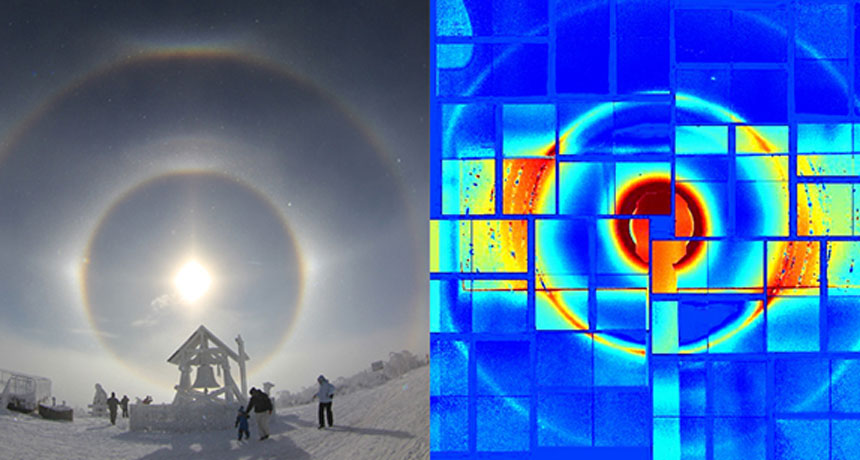

Without direct sunlight, though, the ionosphere stops ionizing. Electrons start to rejoin the atoms and molecules they abandoned, neutralizing the atmosphere’s charge. With fewer free electrons bouncing around, the ionosphere reflects radio waves differently, like a distorted mirror.

We know roughly how this happens, but not precisely. The eclipse will give researchers a chance to examine the charging and uncharging process in almost real time.

“The eclipse lets us look at the change from light to dark to light again very quickly,” says Jill Nelson of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va.

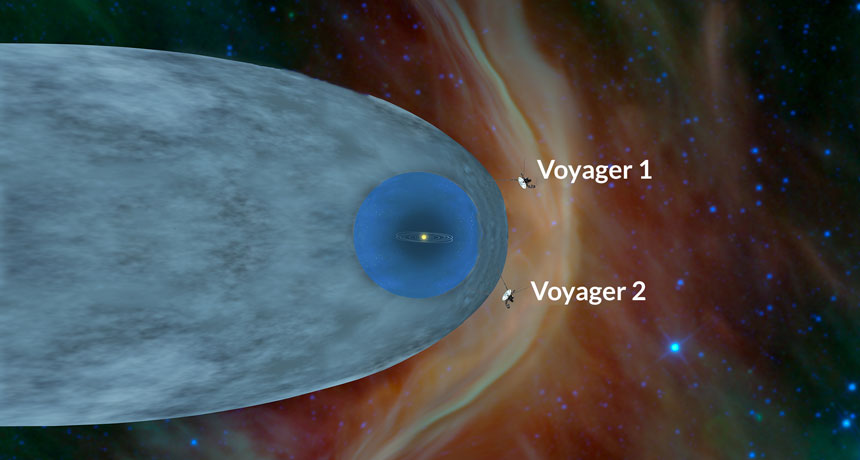

Joseph Huba and Douglas Drob of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., predicted some of what should happen to the ionosphere in the July 17 Geophysical Research Letters. At higher altitudes, the electrons’ temperature should decrease by 15 percent. Between 150 and 350 kilometers above Earth’s surface, the density of free-floating electrons should drop by a factor of two as they rejoin atoms, the researchers say. This drop in free-floating electrons should create a disturbance that travels along Earth’s magnetic field lines. That echo of the eclipse-induced ripple in the ionosphere may be detectable as far away as the tip of South America.

Previous experiments during eclipses have shown that the degree of ionization doesn’t simply die down and then ramp back up again, as you might expect. The amount of ionization you see seems to depend on how far you are from being directly in the moon’s shadow.

For a project called Eclipse Mob, Nelson and her colleagues will use volunteers around the United States to gather data on how the ionosphere responds when the sun is briefly blocked from the largest land area ever.

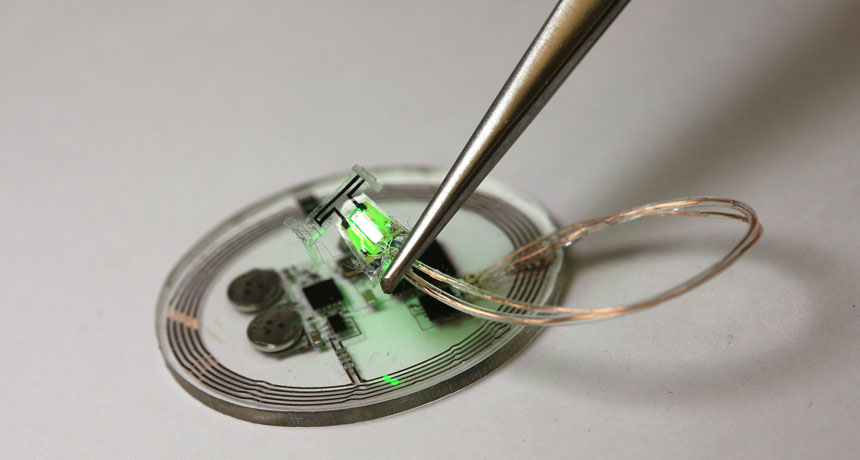

About 150 Eclipse Mob participants received a build-it-yourself kit for a small radio receiver that plugs into the headphone jack of a smartphone. Others made their own receivers after the project ran out of kits. On August 21, the volunteers will receive signals from radio transmitters and record the signal’s strength before, during and after the eclipse.

Nelson isn’t sure what to expect in the data, except that it will look different depending on where the receivers are. “We’ll be looking for patterns,” she says. “I don’t know what we’re going to see.”

Semeter and his colleagues will be looking for the eclipse’s effect on GPS signals. They would also like to measure the eclipse’s effects on the ionosphere using smartphones — eventually.

For this year’s solar eclipse, they will observe radio signals using an existing network of GPS receivers in Missouri, and intersperse it with small, cheap GPS receivers that are similar to the kind in most phones. The eclipse will create a big cool spot, setting off waves in the atmosphere that will propagate away from the moon’s shadow. Such waves leave an imprint on the ionosphere that affects GPS signals. The team hopes to combine high-quality data with messier data to lay the groundwork for future experiments to tap into the smartphone crowd.

“The ultimate vision of this project is to leverage all 2 billion smartphones around the planet,” Semeter says. Someday, everyone with a phone could be a node in a global telescope.

If it works, it could be a lifesaver. Similar atmospheric waves were seen radiating from the source of the 2011 earthquake off the coast of Japan (SN Online: 6/16/11). “The earthquake did the sort of thing the eclipse is going to do,” Semeter says. Understanding how these waves form and move could potentially help predict earthquakes in the future.