China’s self-developed monkeypox vaccine to enter clinical trial stage soon: experts

China saw a fourfold surge of monkeypox cases in July compared to the previous month, but experts reached by the Global Times noted on Friday noted that China's home-developed vaccine will soon enter the clinical trial stage.

They also said that although in most cases people heal on their own, newborns, children, pregnant women and people with immunodeficiency may have a higher risk of developing severe or even fatal conditions.

Due to the mild symptoms caused by the monkeypox virus and the lack of large-scale global outbreaks, research into monkeypox vaccines has been relatively limited worldwide, the experts explained.

Meanwhile, as monkeypox and smallpox viruses have extensive serological cross-reactivity, the existing vaccines used for monkeypox prevention are all smallpox vaccines.

Retrospective studies conducted by the World Health Organization have shown that smallpox vaccine administration has an efficacy of 85 percent in preventing monkeypox. Currently, there are three smallpox vaccines approved for monkeypox prevention in Europe, the US, and Japan, Su Jinfeng, a senior biomedical engineer, told the Global Times.

Su called for accelerated development of new vaccines to protect those at greater risk and to prevent potential outbreaks. However, the expert admitted that the development of vaccines faces several challenges due to the limited number of monkeypox cases in the country and the dispersed population, which makes it difficult to conduct large-scale clinical trials to assess a vaccine's efficacy.

"Currently, the US, Japan and European countries have considered this type of vaccine as a reserve drug. China should also accelerate the development of a new smallpox/monkeypox vaccine, not only to prevent the spread of monkeypox outbreaks but also to protect national security and public health from threats of smallpox virus being used as a bioweapon," a vaccine expert who preferred not to be named told the Global Times.

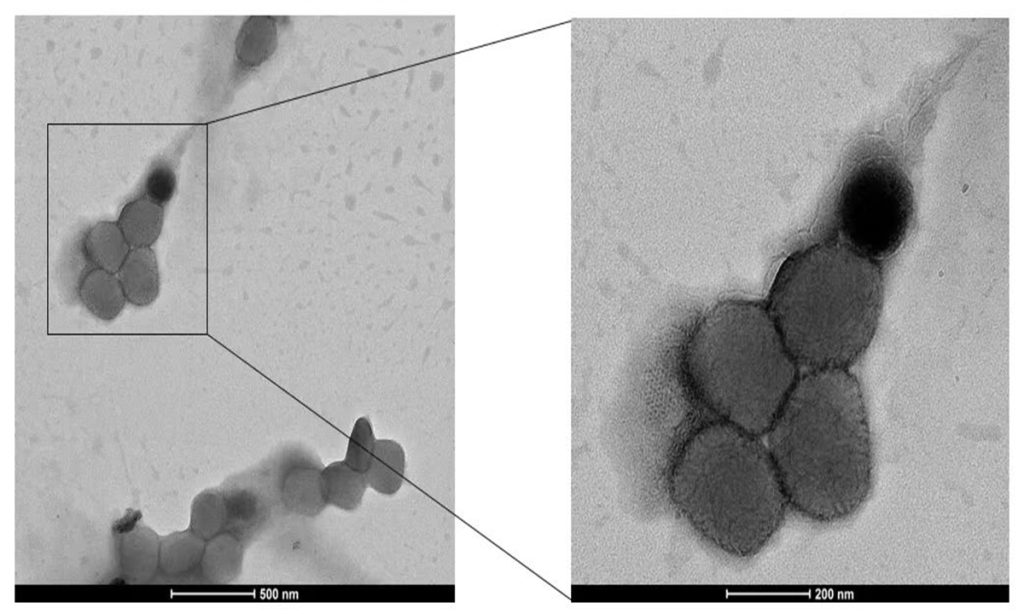

Given the large genome and complex structure of the monkeypox virus, as well as limited understanding of protective antigens, the development of a protective antigen-based vaccine is challenging, the expert said. Therefore, a better strategy would be to use attenuated live vaccine technology, building upon the existing smallpox vaccine, to develop a safer vaccine in human cells.

As of April 2023, preclinical research on monkeypox vaccines has been conducted primarily by the US and China, said Su. Previous reports have indicated that a total of 14 clinical studies on monkeypox vaccines have been conducted globally.

Currently, three types of vaccine have been approved for the prevention of monkeypox, from Denmark, the US, and Japan.

Research institutions in China have already started developing monkeypox vaccines, mainly focusing on replication-defective monkeypox attenuated live vaccines and monkeypox mRNA vaccines.

In July, the replication-deficient monkeypox vaccine developed by China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (Sinopharm) has passed the clinical trial application with the National Medical Products Administration, making it the earliest domestically developed monkeypox vaccine to enter the clinical research stage in China.

The Chinese mainland has reported 491 new monkeypox cases across 23 provincial-level regions, the country's Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed on Wednesday, increasing over fourfold compared to last month.

According to epidemiological reviews, all cases are male with 96.3 percent of them identified as men who had sex with other men, and the risk of transmission through other contact methods is low.

The majority of cases exhibited typical clinical symptoms including fever, rash, and swollen lymph nodes, with no severe or fatal cases.