A new implant uses light to control overactive bladders

A new soft, wireless implant may someday help people who suffer from overactive bladder get through the day with fewer bathroom breaks.

The implant harnesses a technique for controlling cells with light, known as optogenetics, to regulate nerve cells in the bladder. In experiments in rats with medication-induced overactive bladders, the device alleviated animals’ frequent need to pee, researchers report online January 2 in Nature.

Although optogenetics has traditionally been used for manipulating brain cells to study how the mind works, the new implant is part of a recent push to use the technique to tame nerve cells throughout the body (SN: 1/30/10, p. 18). Similar optogenetic implants could help treat disease and dysfunction in other organs, too.

“I was very happy to see this,” says Bozhi Tian, a materials scientist at the University of Chicago not involved in the work. An estimated 33 million people in the United States have overactive bladders. One available treatment is an implant that uses electric currents to regulate bladder nerve cells. But those implants “will stimulate a lot of nerves, not just the nerves that control the bladder,” Tian says. That can interfere with the function of neighboring organs, and continuous electrical stimulation can be uncomfortable.

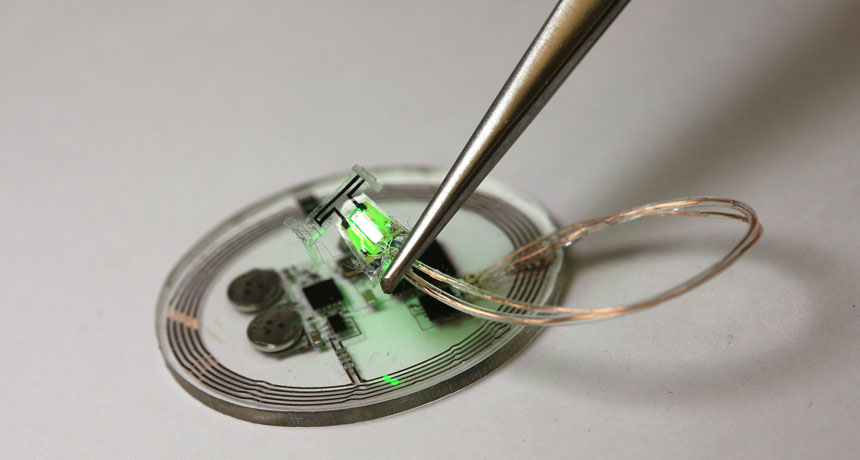

The new optogenetic approach, however, targets specific nerves in only one organ and only when necessary. To control nerve cells with light, researchers injected a harmless virus carrying genetic instructions for bladder nerve cells to produce a light-activated protein called archaerhodopsin 3.0, or Arch. A stretchy sensor wrapped around the bladder tracks the wearer’s urination habits, and the implant wirelessly sends that information to a program on a tablet computer.

If the program detects the user heeding nature’s call at least three times per hour, it tells the implant to turn on a pair of tiny LEDs. The green glow of these micro light-emitting diodes activates the light-sensitive Arch proteins in the bladder’s nerve cells, preventing the cells from sending so many full-bladder alerts to the brain.

John Rogers, a materials scientist and bioengineer at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., and colleagues tested their implants by injecting rats with the overactive bladder–causing drug cyclophosphamide. Over the next several hours, the implants successfully detected when rats were passing water too frequently, and lit up green to bring the animals’ urination patterns back to normal.

Shriya Srinivasan, a medical engineer at MIT not involved in the work, is impressed with the short-term effectiveness of the implant. But, she says, longer-term studies may reveal complications with the treatment.

For instance, a patient might develop an immune reaction to the foreign Arch protein, which would cripple the protein’s ability to block signals from bladder nerves to the brain. But if proven safe and effective in the long term, similar optogenetic implants that sense and respond to organ motion may also help treat heart, lung or muscle tissue problems, she says.

Optogenetic implants could also monitor other bodily goings-on, says study coauthor Robert Gereau, a neuroscientist at Washington University in St. Louis. Hormone levels and tissue oxygenation or hydration, for example, could be tracked and used to trigger nerve-altering LEDs for medical treatment, he says.