Here’s how to use DNA to find elusive sharks

Pulling DNA out of bottles of seawater collected from reefs has revealed some of what biologists are calling the “dark diversity” of sharks.

Physicists have their dark matter, known from indirect evidence since humans can’t see it. Dark diversity for biologists means species they don’t see in some reef, forest or other habitat, though predictions or older records say the creatures could live there.

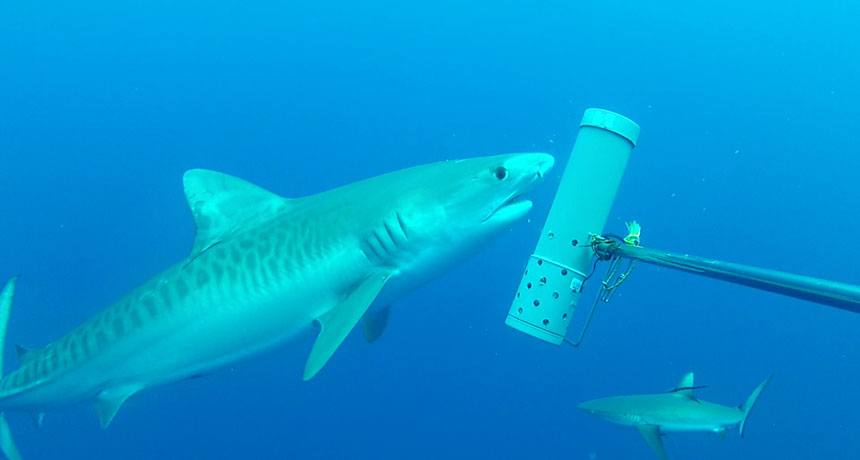

That diversity showed up in a recent comparison of shark sampling methods in reefs in the New Caledonian archipelago, east of Australia. An international team analyzed results from three approaches: sending divers out to count species, baiting cameras and analyzing traces of DNA the animals left in the environment.

Environmental DNA revealed at least 13 shark species — at least six of which failed to show up in the other surveys, the team reports May 2 in Science Advances. With environmental DNA, “you reach the inaccessible,” says marine biologist Jeremy Kiszka of Florida International University in Miami.

The six bonus species found only by DNA included a great hammerhead that might have just been passing through. But the bull shark, silky shark and three other kinds were all plausible as reef residents.

Environmental DNA complements rather than replaces other sampling methods, Kiszka says. The DNA method takes less collecting effort, in this case just 22 bottles of seawater.

Yet these genetic traces give no information about the number of individuals in an area. What’s more, the DNA failed to register three species — tiger, tawny nurse and scalloped hammerhead — that turned up in the other surveys. Even combining all the methods yielded only 16 kinds of sharks. Reports show that 26 shark species once lived in the shallow waters of the archipelago, so 10 remain in the shadows, either having vanished or escaped detection.