A DIY take on the early universe may reveal cosmic secrets

A DIY universe mimics the physics of the infant cosmos, a team of physicists reports. The researchers hope to use their homemade cosmic analog to help explain the first instants of the universe’s 13.8-billion-year life.

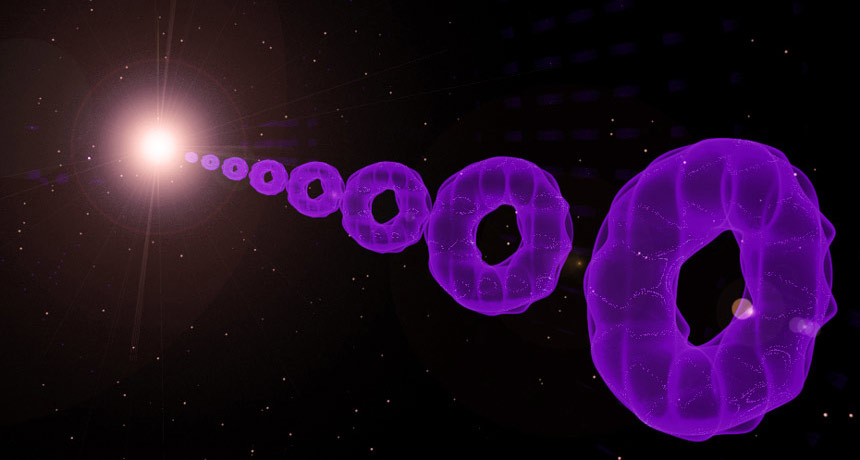

For their stand-in, the scientists created a Bose-Einstein condensate — a state of matter in which atoms are chilled until they all take on the same quantum state. Shaped into a tiny, rapidly expanding ring, the condensate grew from about 23 micrometers in diameter to about four times that size in just 15 milliseconds. The behavior of that widening condensate re-created some of the physics of inflation, a brief period just after the Big Bang during which the universe rapidly ballooned in size (SN Online: 12/11/13) before settling into a more moderate expansion rate.

In physics, seemingly unrelated systems can have similarities under the hood. Scientists have previously used Bose-Einstein condensates to simulate other mysteries of the cosmos, such as black holes (SN: 11/15/14, p. 14). And the comparison between Bose-Einstein condensates and inflation is particularly apt: A hypothetical substance called the inflaton field is thought to drive the universe’s extreme expansion, and particles associated with that field, known as inflatons, all take on the same quantum state, just as atoms do in the condensate.

Scientists still don’t fully understand how inflation progressed, “so it’s hard to know how close our system is to what really happened,” says experimental physicist Gretchen Campbell of the Joint Quantum Institute in College Park, Md. “But the hope is that our system can be a good test-bed” for studying various theories. Already, the scientists have spotted several effects in their system similar to those predicted in the baby cosmos, the team reports April 19 in Physical Review X.

As the scientists expanded the ring, sound waves that were traveling through the condensate increased in wavelength. That change was similar to the way in which light became redshifted — stretched to longer wavelengths and redder colors — as the universe enlarged.

Likewise, Campbell and colleagues saw a phenomenon akin to what’s known as Hubble friction, which shows up as a decrease in the density of particles in the early universe. In the experiment, this effect appeared in the guise of a weakening in the strength of the sound waves in the condensate.

And inflation’s finale, an effect known as preheating that occurs at the end of the rapid expansion period, also had a look-alike in the simulated universe. In the cosmic picture, preheating occurs when inflatons transform into other types of particles. In the condensate, this showed up as sound waves converting from one type into another: waves that had been sloshing inward and outward broke up into waves going around the ring.

However, the condensate wasn’t a perfect analog of the real universe: In particular, while our universe has three spatial dimensions, the expanding ring didn’t. Additionally, in the real universe, inflation proceeds on its own, but in this experiment, the researchers forced the ring to expand. Likewise, there were subtle differences between each of the effects observed and their cosmic counterparts.

Despite the differences, the analog universe could be useful, says theoretical cosmologist Mustafa Amin of Rice University in Houston. “Who knows?” he says. “New phenomena might happen there that we haven’t thought about in the early universe.”

Sometimes, when research crosses over between very different systems — such as Bose-Einstein condensates and the early universe — “sparks can fly,” Amin says.