Does the corona look different when solar activity is high versus when it’s low?

Carbondale, Ill., is just a few kilometers north of the point where this year’s total solar eclipse will linger longest — the city will get two minutes and 38 seconds of total darkness when the moon blocks out the sun. And it’s the only city in the United States that will also be in the path of totality when the next total solar eclipse crosses North America, in 2024 (SN: 8/5/17, p. 32). The town is calling itself the Eclipse Crossroads of America.

“Having a solar eclipse that goes through the entire continent is rare enough,” says planetary scientist Padma Yanamandra-Fisher of the Space Science Institute’s branch in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif. “Having two in seven years is even more rare. And two going through the same city is rarer still.”

That makes Carbondale the perfect spot to investigate how the sun’s atmosphere, or corona, looks different when solar activity is high versus low.

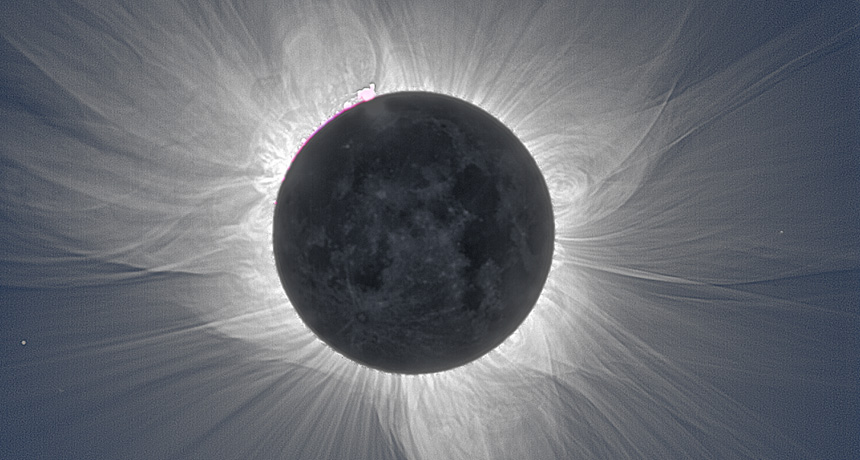

Every 11 years or so, the sun cycles from periods of high magnetic field activity to low activity and back again. The frequency of easy-to-see features — like sunspots on the sun’s visible surface, solar flares and the larger eruptions of coronal mass ejections — cycles, too. But it has been harder to trace what happens to the corona’s streamers, the long wispy tendrils that give the corona its crownlike appearance and originate from the magnetic field.

The corona is normally invisible from Earth, because the bright solar disk washes it out. Even space telescopes that are trained on the sun can’t see the inner part of the corona — they have to block some of it out for their own safety (SN Online: 8/11/17). So solar eclipses are the only time researchers can get a detailed view of what the inner corona, where the streamers are rooted, is up to.

Right now, the sun is in a period of exceptionally low activity. Even at the most recent peak in 2014, the sun’s number of flares and sunspots was pathetically wimpy (SN: 11/2/13, p. 22). During the Aug. 21 solar eclipse, solar activity will still be on the decline. But seven years from now during the 2024 eclipse, it will be on the upswing again, nearing its next peak.

Yanamandra-Fisher will be in Carbondale for both events. This year, she’s teaming up with a crowdsourced eclipse project called the Citizen Continental-America Telescope Eclipse experiment. Citizen CATE will place 68 identical telescopes along the eclipse’s path from Oregon to South Carolina.

As part of a series of experiments, Yanamandra-Fisher and her colleagues will measure the number, distribution and extent of streamers in the corona. Observations of the corona during eclipses going back as far as 1867 suggest that streamers vary with solar activity. During low activity, they tend to be more squat and concentrated closer to the sun’s equator. During high activity, they can get more stringy and spread out.

Scientists suspect that’s because as the sun ramps up its activity, its strengthening magnetic field lets the streamers stretch farther out into space. The sun’s equatorial magnetic field also splits to straddle the equator rather than encircle it. That allows streamers to spread toward the poles and occupy new space.

Although physicists have been studying the corona’s changes for 150 years, that’s still only a dozen or so solar cycles’ worth of data. There is plenty of room for new observations to help decipher the corona’s mysteries. And Yanamandra-Fisher’s group might be the first to collect data from the same point on Earth.

“This is pure science that can be done only during an eclipse,” Yanamandra-Fisher says. “I want to see how the corona changes.”