Climate change could exacerbate economic inequalities in the U.S.

Climate change may make the rich richer and the poor poorer in the United States.

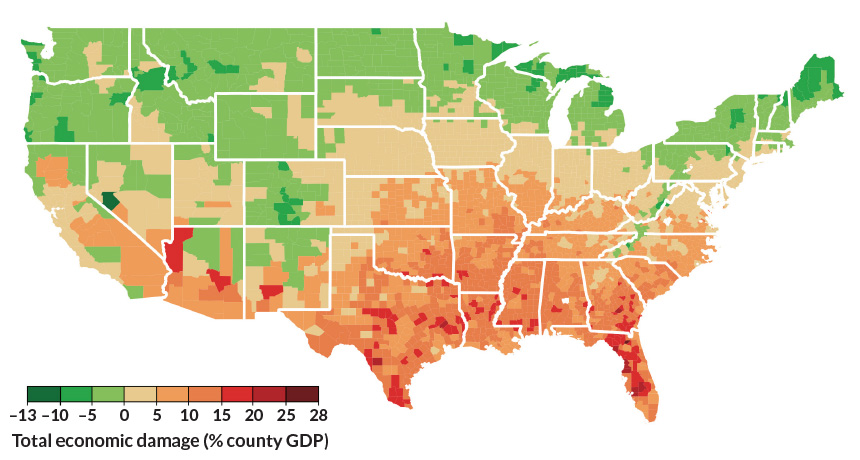

Counties in the South face a higher risk of economic downturn due to climate change than their northern counterparts, a new computer simulation predicts. Because southern counties generally host poorer populations, the new findings, reported in the June 30 Science, suggest that climate change will worsen existing wealth disparities.

“It’s the most detailed and comprehensive study of the effects of climate change in the United States,” says Don Fullerton, an economist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who was not involved in the work. “Nobody has ever even considered the effects of climate change on inequality.”

Researchers created a computer program called SEAGLAS that combined several climate simulations to forecast U.S. climate until 2100, assuming greenhouse gas emissions keep ramping up. Then, using data from previous studies on how temperature and rainfall affect several economic factors — including crop yields, crime rates and energy expenditures — SEAGLAS predicted how the economy of each of the 3,143 counties in the United States would fare.

By the end of the century, some counties may see their gross domestic product decline by more than 20 percent, while others may actually experience more than a 10 percent increase in GDP. This could make for the biggest transfer of wealth in U.S. history, says study coauthor Solomon Hsiang, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

In general, SEAGLAS predicts that counties in the lower Midwest, the South and the Southwest — already home to some of the country’s poorest communities — will bear the brunt of climate-caused economic damages, while counties in New England, the Great Lakes region and the Pacific Northwest will suffer less or see gains. For many of the examined economic factors, such as the number of deaths per year, “getting a little bit hotter is much worse if you’re already very hot,” explains Hsiang. “Most of the south is the hottest part of the country, so those are the regions where costs tend to be really high.”

The economic gaps may get stretched even wider than SEAGLAS predicts, Fullerton says, because the simulation doesn’t account for wealth disparities within counties. For example, wealthier people in poor counties may have access to air conditioning while their less fortunate neighbors do not. So blisteringly hot weather is most likely to harm the poorest of the poor.

Not all researchers, however, think the future is as bleak as SEAGLAS suggests. The simulation doesn’t fully account for adaptation to climate change, says Delavane Diaz, an energy and environmental policy analyst at the Electric Power Research Institute in Washington, D.C., a nonprofit research organization. For example, people in coastal regions could mitigate the cost of sea level rise by flood-proofing structures or moving inland, she says.

And the economic factors examined in this study don’t account for some societal benefits that may arise from climate change, says Derek Lemoine, an economist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. For instance, although crime rates rise when it’s warmer because more people tend to be out and about, people being active outside could have a positive impact on health.

But SEAGLAS is designed to incorporate different societal variables as new data become available. “I really like the system,” Lemoine says. “It’s a super ambitious work and the kind of thing that needs to be done.”